Dying in Scotland

A feminist issue

Kezia Dugdale - Former leader of the Scottish Labour Party

Kezia Dugdale - Former leader of the Scottish Labour Party

Most will be familiar with the maxim that ‘the personal is political’. Often this is spoken about with regards to how we live, but rarely with regards to how we die.

This report focuses specifically on the voices of women – telling us loud and clear how the current laws around dying in Scotland affect them and why those laws need to change. We now know women’s experiences are too often dismissed and their wishes overlooked. We must examine how gender affects all elements of health – and this includes end-of-life care and choices.

Change comes when the voices of people who live under the injustice of a bad law come together to expose its cruelty. This is the lesson we learn when we look back on the past – on women’s suffrage and civil rights, as well as recent reforms on equal marriage and reproductive rights.

It takes movements of people to shift the power balance back to dying people and their loved ones. Sometimes it feels like change is happening too slowly, or not at all. But the movement for the right to die with dignity is strong - rooted in compassion and empowerment, and I believe assisted dying will be Scotland’s next progressive reform.

79% of women think that the next Scottish parliament should debate changing the law on assisted dying (YouGov 2020). Scottish women want change, and Scottish parliamentarians have the responsibility to listen and take action.

I’d never thought about dying as a feminist issue, but after reading this report it’s clear to me that the law in Scotland is failing women.

There’s nothing feminist about making women watch their loved ones suffer.

There’s nothing feminist about allowing only those who can afford £10,000 to go to Dignitas.

There’s nothing feminist about denying dying women and their families choice at the end of their lives.

There’s nothing feminist about the status quo.

Good Deaths

Women in Scotland want to talk openly about dying with their loved ones, which is something they feel able to do. However, interviewees said they had not had frequent conversations with their doctors about end-of-life care.

Some said they often didn’t feel involved in decision making and most said said that having openness and honesty between themselves and healthcare professionals was difficult.

“Sometimes I feel like I’d like to speak to my own doctor about it [death], but they don’t have time…

Maybe when things get worse I’ll talk to her then.”

- Woman with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Echoing previous research on the topic, women said that a good death is one which is pain-free, in a location of their choosing and one with dignity.

The concept of a good death, for some of our interviewees, was synonymous with dying at home with minimal interference. However, in reality this wasn’t always possible.

“The only concern I had was that he [my father] would be in distress or in pain at the end. You don’t know what’s going to happen. At least in hospital you can administer pain relief straight away. It was a trade-off. He might be more uncomfortable and in pain [at home] but at least it was on his own terms and he would be alone [without interference].

Right at the end we did call in the nurses because we panicked. They administered morphine and he passed away. She [my sister] apologised for calling them. She feels guilty about that. But she didn’t want him to suffer so called them right at the last minute. We weren’t strong enough to see his wishes through so I feel guilty about that.”

- Carer

For other women, the location of their death was an important consideration when thinking about what a good death meant for them, but they had made a conscious decision not to die at home.

“I have chosen not to die at home. I would prefer that but for my great grandson, who is five, it’s not ideal.”

- Woman with cancer

Bad deaths

Pain is one of the biggest concerns for

both informal carers and dying women and

not knowing whether they might be in pain

at the end of life causes a great deal of

anxiety and stress.

He [my husband] was in a lot of pain. I don’t think the doctors ever really got on top of the pain management in the end. They tried. But it was a balancing act between keeping him pain free, and he was never pain free in the last 3 months, and trying to keep his brain compos mentis without him being too sleepy.”

- Carer

A lack of communication and shared decision-making was highlighted by one interviewee who said that she wasn’t sure whether the doctor treating her mother-in law at the end of life gave her morphine to hasten her death.

“I remember my mother-in-law died of cancer and she had a good death in a way, she was in her own home and we were all there when she died. She was in lots of pain. We were waiting for a syringe pump. She was crying with the pain. The doctor gave her a morphine jab and she didn’t wake up. I was grateful for that. I can’t be sure can I? But I think he thought it was time - we were all there.”

- Carer

The European Association for Palliative Care states that ‘some physicians administer doses of medication, ostensibly to relieve symptoms, but with a covert intention to hasten death.’ While we can’t be sure whether the doctor’s intention was to end life or not, it highlights a lack of transparency about treatment decisions at the end of life which can be disempowering and disorienting for those left behind.

Women are particularly worried about how a lack of choice at the end of life will affect their families.

I want to live my life until the last breath.

I’m dying but I want to be living until the final moment of death. But I want that final moment of death not to traumatise my family … even if I’m sedated it’s the fact that my family will have to endure that.

That’s the bit that haunts me.”

- Kay, who has a terminal illness

Gaslighting

Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation where one person causes another to question their memory, perception of reality or their judgements.

The practice of medical gaslighting, where healthcare professionals convince someone that they are exaggerating their symptoms, or perhaps imagining them altogether, is closely linked to the culture of paternalism in medicine.

While anyone can be a victim of gaslighting, women are more likely to be on the receiving end of it. A recent review into three medical scandals showed that women were given medical products that weren’t properly tested, and then weren’t believed when they complained of side effects. The report showed that the women’s voices were consistently dismissed and were routinely not believed when speaking about their symptoms, setting an unequal tone for the doctor-patient relationship, with no room for genuine shared decision making.

This chimes with other research, with studies finding that women are less likely to be given pain relief than men, have to wait longer to receive pain relief, and are more likely to be given sedatives rather than pain relief.

For women living at the intersection of sexism and racism, the situation is worse, with one US study showing that women who identified as Black or Hispanic received less pain relief following childbirth than white women, while in the UK Black women are five times more likely to die in pregnancy than white women.

WHO CARES FOR

PEOPLE AT THE

END OF LIFE?

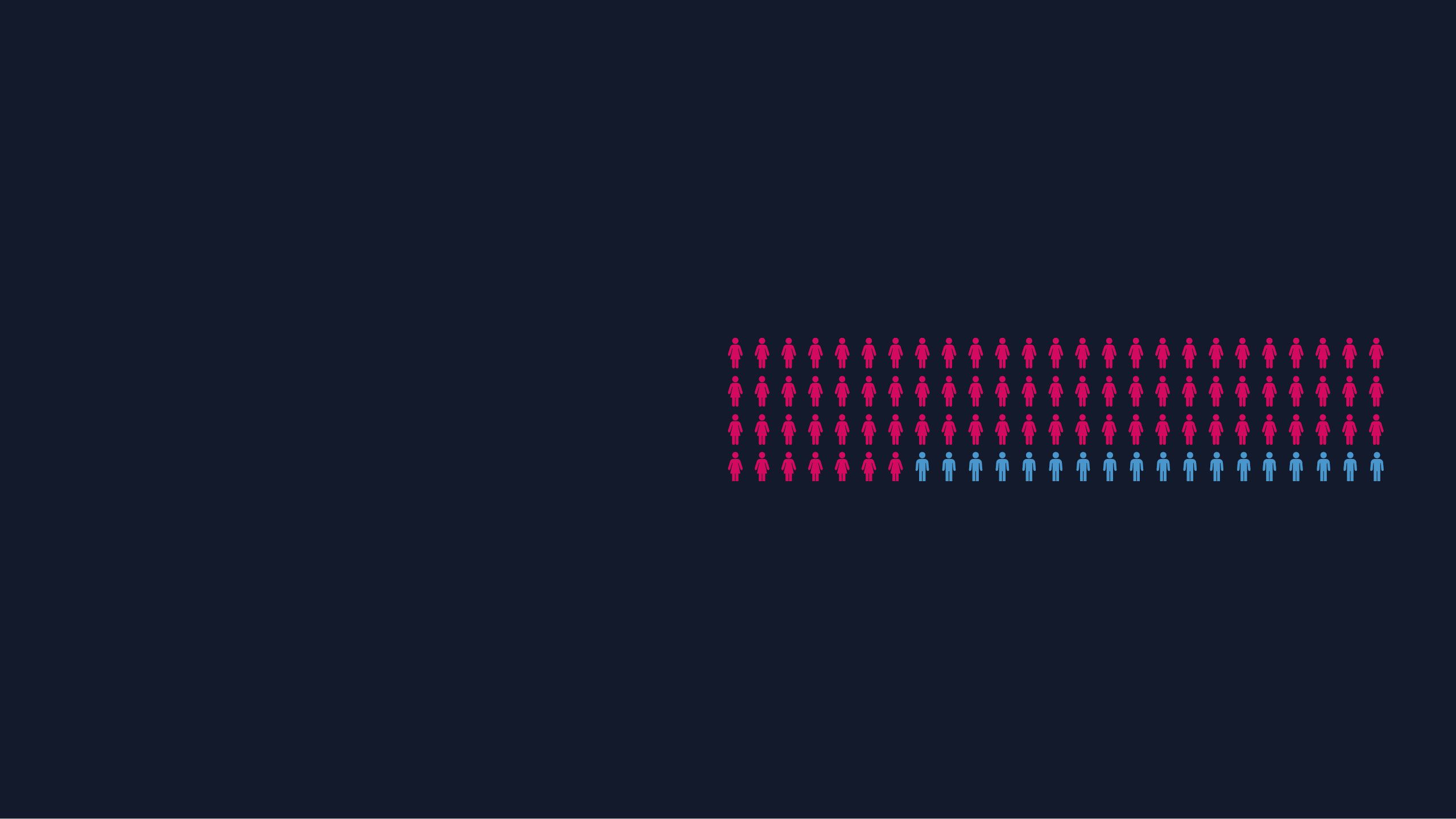

In Scotland, there are 759,000 adult carers, 59% of whom are women.

Cultural norms have meant that women are often expected to take on caring responsibilities. The role of informal carer was something that interviewees said they naturally fell into, and were happy to do.

“It was totally my responsibility as being his wife and the fact that I’m younger than him. I wasn’t working either. I was young, fit, and capable to look after him. There was no hesitation whatsoever to take on that caring role.”

- Carer

Women face practical and emotional challenges when taking on a caring role. For example, the women interviewed said they had to organise unpaid leave or flexible working to be able to deliver medicine at set times and some moved house to be near their loved one. Many struggled as they saw partners ‘turn into another person’ and did not know how to manage the changes in their behaviour and mood. Other research has found that women carers have higher levels of stress, worse physical health, higher levels of depression and anxiety, and are more likely to live in poverty than male carers.

The majority of carers are women and when this is coupled with the desire to care for people in their own homes and the blanket ban on assisted dying, we can infer that many women witness the distressing end-of-life symptoms that some people suffer at the end of life and bad deaths at a disproportionate rate to men. Witnessing traumatic deaths can increase the likelihood of complex grief and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It was quite hard seeing him go from my dad to not himself. It was horrible to watch that transformation from someone being the person you know to someone being an alive dead person.”

- Carer

The Royal College of Nursing, which represents nurses in the UK, has been neutral on assisted dying since 2009, following an extensive consultation with its members. The RCN has also published guidance on responding to requests to hasten death, recognising that it is hard for nurses to know how to respond:

“Nurses, and other health and social care practitioners may feel uncomfortable or unsure about how to respond to such situations, and may feel inadequately prepared to engage in these conversations in case they say ‘the wrong thing’ in response.

They may also feel concerned about their legal position and be anxious about potential professional sanctions. As a consequence, they may close down the communication quickly, leaving the patient – or those important to them – feeling isolated and with no outlet for discussing their needs and concerns.”

It’s therefore not only unpaid carers who witness the effects of a lack of choice at the end of life in Scotland, but also nurses – the majority of whom are women.

“The terror in his [my husband’s] eyes and seeing the pain in his eyes. He would beg myself, the nurses, and family members to just knock him out.”

-Liz, whose husband died of cancer

“I had been a nurse for over 25 years, and I have nursed all these people right through to their last breaths. But when it came to my mum, I couldn’t help, and I had to watch her going through a pulmonary embolism.

And people say, when you die of a pulmonary embolism it takes 20 to 30 minutes to travel through the lungs and reach the heart. And that 20 to 30 minutes was very traumatic to watch.”

- Kay, who has a terminal illness

Dignitas

Some women wish to retain an element of control over dying by travelling abroad to organisations like Dignitas and Life Circle to have an assisted death.

Dignitas – to live with dignity, to die with dignity - is a Swiss non-profit members’ society providing assisted dying for those who are terminally or incurably ill.

Elaine, who accompanied her husband Richard to Dignitas in 2019, has spoken about how difficult it was to watch her terminally ill husband arrange a trip to Dignitas himself:

“It’s a horrible thing to go through, as his partner. Going to Switzerland is not something we want to have to do. If I could keep him for even one more day that would be great but he’s got to be able to do everything himself - he’s got to travel and administer the medication himself. They are making him choose to go early because he’s afraid that the choice is going to be taken from him and he wants to avoid a prolonged death.”

Despite fear of prosecution, women are prepared to take the risk of facing legal consequences in order to help their loved ones have an assisted death abroad.

“If he [my dad] had wanted that, I would have done it anyway, whether I was prosecuted or not. A prosecution is a thing that will come and go whereas potentially making my dad really upset by not taking him would be something that would never leave me.”

- Carer

Alongside this there was a strong sense of the injustice of the current situation and a recognition that dying people shouldn’t have to travel overseas at great cost or with the worry of potential legal consequences for their loved ones who help them, in order to get the death they want:

“I don’t have £10,000 and why should I have to go there when I’ve lived my life here?”

- Woman with Parkinson's Disease

“I couldn’t afford to go to Dignitas, but that would be my choice if I could.”

- Woman with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Although there is no specific law against assisting a suicide in Scotland, those who accompany a loved one overseas for an assisted death could face prosecution for culpable homicide or for culpable and reckless conduct.

“I feel so sorry for them, that they’ve had to travel in a very unwell state – they should be able to do it in the privacy and sanctity of their own homes…

Also the worry of your loved one facing prosecution, my goodness that’s ridiculous. How heart-breaking, you are making the ultimate journey knowing they won’t come back alive. There can be no greater act of love I guess.”

- Carer

Some who were unable to travel to Switzerland experienced terrible suffering and asked their families for help to die at home, which would have had severe legal consequences. Some women told us they were left with a terrible sense of guilt for not helping a loved one end their life when they begged them to:

“There were times when she [my mum] said she’d had enough. She told us and she told the staff at the hospice. She was anxious and she was in pain and she wasn’t going to get any better … She said ‘just kill me now’. Imagine feeling guilty that you didn’t help kill your mum. Can you imagine what would have happened to us if we’d done that?”

- Victoria, whose mum died of cancer

The Law Women Want

Over 150 million people around the world live in a place where some form of assisted dying is legal, including in numerous states in the USA, across Canada and the Australian states of Victoria and Western Australia.

As more jurisdictions around the world change their laws, people in Scotland recognise they are being denied genuine choice over their death.

“What’s so different about America? What’s so different about Australia? We should be looking at this”.

- Carer

Women were also clear that they wanted a law that would provide them with agency over their body.

“We’ve made choices all through our lives. We have made choices for our children as parents. And the last choice that we should make is how and in which shape and form we should pass away.”

- Kay, who has a terminal illness

“Someone has agency throughout their whole life but at the end of their life we go ‘well hang on a second - this isn’t up to you anymore’. I think it’s completely reasonable and sensible to allow people to continue to have that agency over their own life. We have that agency every day. But at the end of my life someone could say we’re taking that choice away from you now. If we have the law, it’s giving people the choice back.”

- Carer

The fight to have control over your body is something that rings true for many disabled women too.

“For me, as a visually impaired person, so many things are taken away from you in terms of choices. Like you have to fight to have information in accessible formats. You have to fight to be able to get into places. I don’t want to fight to know when to finish my time if I know that time is going to happen anyway. We live in a society where we say choice is really important and yet we don’t give people certain choices.”

- Kirin, whose husband died of cancer

As explored at the beginning of this report, women think a good death is one which is pain free, in a place of their choosing, and one with dignity. However, having a good death wasn’t something they felt they could predict or prepare for, and they were frustrated about the lack of control they had over the factors that make a good death. In Oregon, where assisted dying has been legal for over 20 years, a third of patients who formally request assisted dying do not take the life-ending medication, showing that they have the prescription as an ‘insurance policy’ if their suffering becomes unbearable. This provides reassurance and peace of mind to dying people and their loved ones which in turn helps them to have a better death.

The interviewees felt that the introduction of an assisted dying law in Scotland would allow dying women to control their death and take away some of the anxiety women are faced with at the end of life. However, the interviewees also recognised the need for strict safeguards.

“I’d want to ensure that there was a rigid interview process with the patient and the patient’s family, a multidisciplinary team not just a medical case review … I thought about this as a care worker when I was younger, I saw a lot people dying of cancer and got a good idea of what a good death and what a bad death was. If they could have died with dignity before that point, they would have taken it.”

- Carer

The law Dignity in Dying is campaigning for in Scotland would allow terminally ill, mentally competent adults the option of assisted dying. Two doctors would independently assess whether the person is of sound mind and terminally ill. These doctors would independently explore the reasons for the request for assisted dying and ensure the person is aware of all their other options.

If the person is eligible, the doctor would write the prescription for the life-ending medication. The patient would take this medication themselves. This is similar to the Death with Dignity Act in Oregon, which has worked safely for over 20 years and has been adopted by many other American states such as California and Washington, as well as in the Australian state of Victoria.

“I think some people jump up and down and oppose this because they don’t look at the detail. They’re not willing to say, well if it’s safe then why not?”

- Woman with breast cancer

What needs to change?

Based on this report, it’s clear things must change.

We need to...

Listen to women

Many women have been at the forefront of progressive causes; challenging harmful status quos in order to achieve autonomy and bodily integrity around pain relief in childbirth, freedom from violence, and reproductive choice, including the option of abortion, as well as for financial independence and the right to work and participate in public life. Yet dying women do not have choice over how and when they die.

This is despite polls showing that 80%-87% of Scottish women support a change in the law to allow terminally ill adults the choice of an assisted death. Just 6% of Scottish women think the UK’s current laws prohibiting assisted dying are working well.

Allowing those who can afford Dignitas to control their deaths while failing to address the law in Scotland is a cruel and ineffective policy, and one which must urgently change. While £10,000 is a financial barrier for many, women are more likely to be living in poverty than men and are therefore less likely to have the financial means to have an assisted death abroad. In Scotland, women are paid on average 15% less per hour than men and the poverty rate of lone mothers is 39%. The rates of poverty in Scotland are even higher for Black and minority ethnic women and for disabled women.

If we are to move towards a medical culture where individuals are empowered and supported by doctors to make decisions about their own care, then assisted dying must be an option provided under good end-of-life care. For too long, politicians and healthcare professionals have decided what happens to women’s bodies, and they still have the power to decide how women die.

It is clear from what women have told us that they have moved beyond questioning if Scotland should have an assisted dying law and instead questioned when this change will come and how the law would work in practice. MSPs must follow suit and move beyond debating whether assisted dying is right or wrong, and instead focus on making a law that empowers women at the end of life.

Provide the right support

Women told us that being able to choose the location of death was a way to make a good death more likely for themselves or their loved ones.

The place someone wishes to be cared for and where they want to spend their remaining time should be respected, but this has created new social pressures on women to ensure a pain-free and dignified home death for the person they are caring for. The pressure for people to die at home has been shown to result in complicated bereavement for carers, particularly if the person has to be admitted into a hospital, care home or hospice, and can result in feelings of guilt if their loved one’s wishes weren’t able to be followed.

The emphasis on dying at home shifts dying from public spaces to private spaces. While this may be desirable for many, the ideal of dying at home keeps death behind closed doors and shifts the responsibility of ensuring dying people have good deaths to their carers, the majority of whom are women. Many of the informal carers interviewed accessed support from organisations like Macmillan Cancer Support who gave them invaluable tools and advice, but still felt overwhelmed by the practical and emotional challenges of caring for someone. While being an informal carer for someone dying at home can be challenging for many women, for women who are dying, the decision about where to be cared for can be difficult too. Embedded in the notion of a good death being a home death is the assumption that home is the best place to die, which is not the case for many. Houses which are damp, cold and with little food in the fridge may not be the place someone wishes to die. Other women choose not to die at home because they don’t want their loved ones to have the memory of them dying there.

It is vital that Scottish politicians ensure that the right support is provided to those who want to die at home and the women who are caring for them. But we must be careful not to stigmatise dying in hospices, care homes and hospitals in Scotland, and explore different end-of-life care settings with dying people and their carers, making sure their needs are properly understood and supported. This can include exploring what priorities lie behind someone’s wish to die at home, and seeing if there are ways to make other locations fulfil these desires.

Modernise end-of-life culture

Given that women have such strong feelings about what makes a good death, it is not surprising that women are less likely to state a preference to receive life-prolonging treatment than men. This in turn means that men receive more aggressive, non-beneficial treatment and more hospital admissions at the end of life.

Dignity in Dying Scotland’s sister organisation Compassion in Dying supports people to think through and plan any treatments they would and wouldn’t want to receive at the end of their life. In the second half of 2019, 73% of people who called the free information line identified as female and 27% identified as male. However, in the wider population the uptake of planning ahead tools such as Advance Directives and Powers of Attorney for both men and women is very low. Mainstreaming advance care planning, and ensuring that healthcare professionals have the skills and confidence to discuss end-of-life issues with their patients will ultimately benefit everyone with patients more likely to get the care and treatment that’s right for them at the end of life, and healthcare professionals more able to provide care that is in keeping with their patients’ wishes and values.

Women told us that being in pain was their biggest concern. This fear is not unfounded; research has shown that even if every dying person who needed it had access to the level of care currently provided in hospices, 591 people in Scotland a year would still have no relief of their pain in the final three months of their life, equating to 11 Scots every week. This is despite Scotland being positioned among the top 10 EU countries for the level of provision of specialist palliative care services.

If we are to improve current end-of-life culture, healthcare professionals must be held to account for gaslighting. When Dignity in Dying Scotland released the report ‘The Inescapable Truth’ detailing how 11 Scots a week suffer as they die, the report was met with resistance from palliative care professionals who reported that relatives were mistaking normal end-of-life symptoms for more distressing symptoms, making bereaved relatives question what they had seen. While some palliative care professionals recognise that a minority of terminally ill people die in pain, many have argued, in response to calls to legalise assisted dying, that the answer is simply to improve end-of-life care. This argument has also been made in debates in Holyrood. Advocating for more palliative care as an alternative to assisted dying ignores the reality that for many people, no amount of palliative care is enough to relieve their suffering. This is in itself a form of gaslightling.

Bad deaths are currently inevitable. Women deserve open and honest conversations about the reality of dying in Scotland and their voices should not be silenced when they speak out about the failures of the current law.

CONCLUSION

Dignity in Dying Scotland is campaigning for a change in the law so that assisted dying is an option for all adults who are terminally ill and mentally competent. This report considers the need for a change in the law on assisted dying in the light of women’s views and experiences.

Women have made their point clear – the law in Scotland is not working for them or their loved ones. They witness needless suffering at the end of life and are anxious about their own deaths given the lack of choice available to them in Scotland. They are also overwhelmingly supportive of a change in the law on assisted dying for terminally ill, mentally competent adults.

It is now time for politicians to look at the issues outlined in this report and respond accordingly, by mainstreaming advance care planning and by legislating for greater choice and control at the end of life, including the option of assisted dying under strict safeguards. Assisted dying is an issue on which the Scottish public is united. Scottish politicians can lead the way to a progressive future for dying women and their families.

Scotland has the opportunity to spearhead this liberal reform, showing that it is a country truly committed to choice at the end of life.