TIME FOR CHOICE

Banning assisted dying vs legalising assisted dying

Unsafe

• Up to 650 dying people take their own lives every year

• Dying people attempt to end their lives while receiving specialist palliative care

• A desire to protect loved ones leads to dying people taking their lives alone

Safe

• Clear, upfront safeguards including medical oversight

• Dying people have a safe alternative to violent or inexact methods

• Vulnerable people are better protected when there is a legal framework in place

Unfair

Fair

Unregulated

Regulated

In the UK, the absence of a legal, safeguarded option of assisted dying inflicts significant harm on dying people and their families. 78% of the public want this to change. (YouGov 2023)

- Dying people are ending their own lives in this country. These deaths are often violent and lonely.

- Dying people are suffering as they die because palliative care, no matter how good, cannot relieve all suffering all of the time.

- Dying people are traveling overseas for an assisted death. This option is not available to everyone, and the law does not offer any protection to individuals or loved ones who provide support.

Over 250 million people around the world now have access to some form of safeguarded assisted dying law. There is no evidence of abuse of these laws and extensive evidence to show that they address the failings created by a blanket ban on assisted dying.

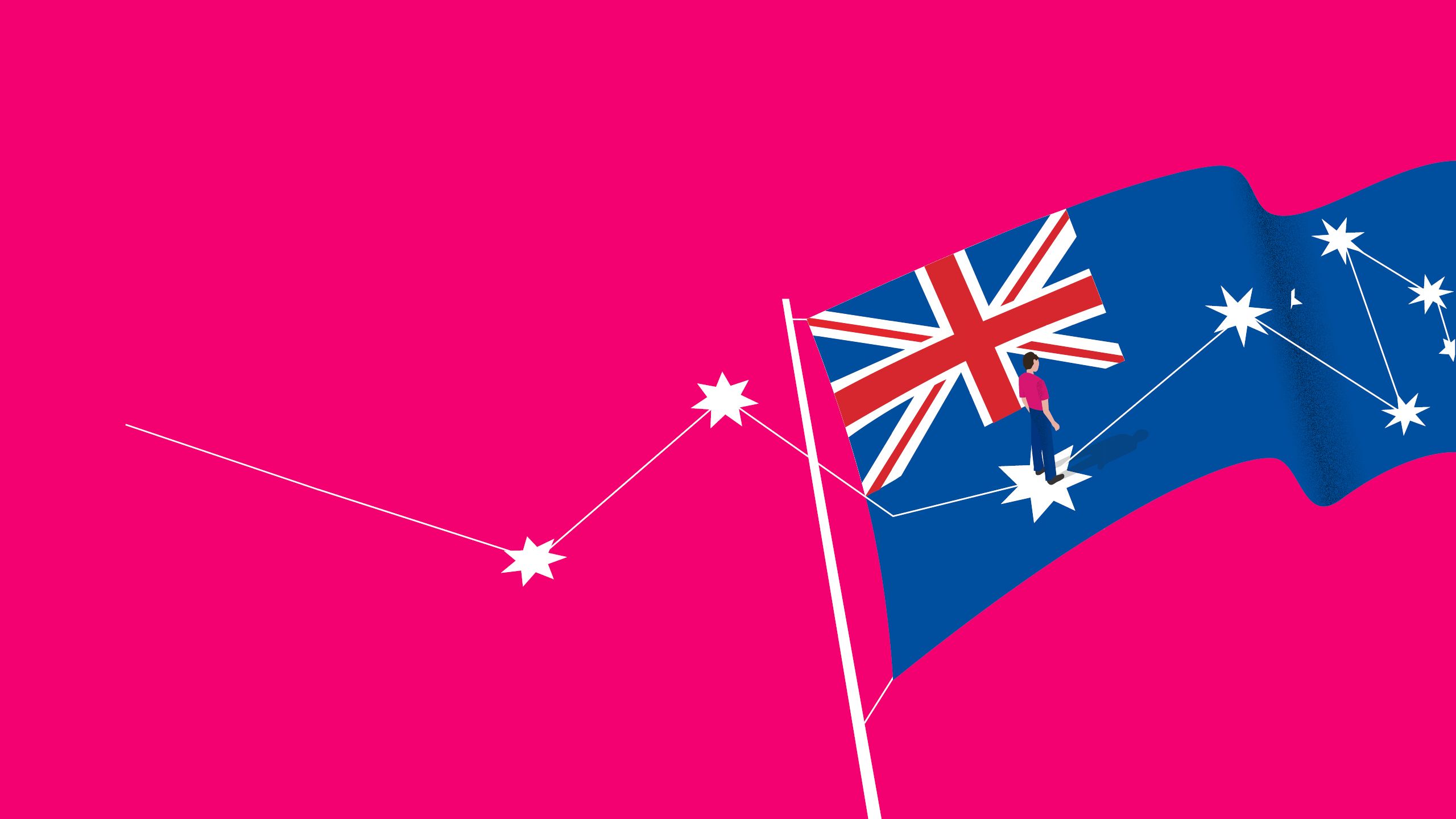

In Australia, Victoria became the first state to pass assisted dying legislation in 2017, after nearly three years of research and consultation. The remaining five Australian states have all now passed assisted dying laws. Assisted dying also came into effect in New Zealand in 2021 following a public referendum. These laws provide the option of assisted dying for terminally ill, mentally competent adults. They contain strict, upfront safeguards, including assessments by at least two independent doctors.

Australian assisted dying laws are based on the law in Oregon, where assisted dying has been legal since 1997. Ten US states and Washington, DC have followed Oregon’s lead.

This report explores the difference that assisted dying legislation can make for dying people and their families.

Dignity in Dying is campaigning to make end-of-life care safer and more compassionate with the introduction of an assisted dying law. This will give terminally ill, mentally competent adults the option of controlling the manner and timing of their deaths within a robust legal framework that protects everyone in society.

Bringing forward this debate is a matter of urgency for Parliament. Further delay causes intolerable suffering for dying people and their loved ones.

It is time for Westminster to have this debate.

It is time for choice.

It’s time we did better for dying people in the UK.

UNSAFE: FORCING PEOPLE TO ACT IN SECRET

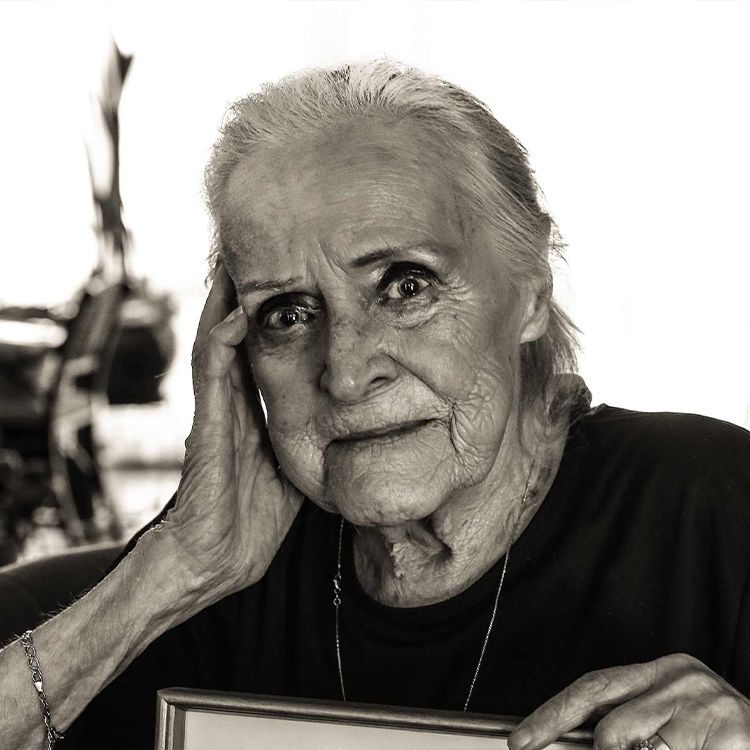

Bob Pawsey, from Buckinghamshire, died of lung cancer in July 2022.

His daughter Liz recalls how Bob attempted to end his life with a drug overdose that caused temporary psychosis before he died in a nursing home four months later.

Bob Pawsey and his daughter Liz

In the last year of his life my dad was in constant pain, he could barely sleep and his weight dropped to just 6 stone.

He was just skin and bone, it was truly terrible to see.

One night my mum found him unconscious on his bedroom floor after taking an overdose to end his life. At the hospital they gave him medication to reverse the overdose and he was screaming in pain. The overdose caused a week-long psychosis that left him agitated and confused.

He was in and out of hospital in those final months and constantly told us he wanted to die. He tried to take control of his death in the only way he could, but it meant he suffered in his final months. That’s not how he wanted his life to end.

Bob Pawsey and his daughter Liz

Bob Pawsey and his daughter Liz

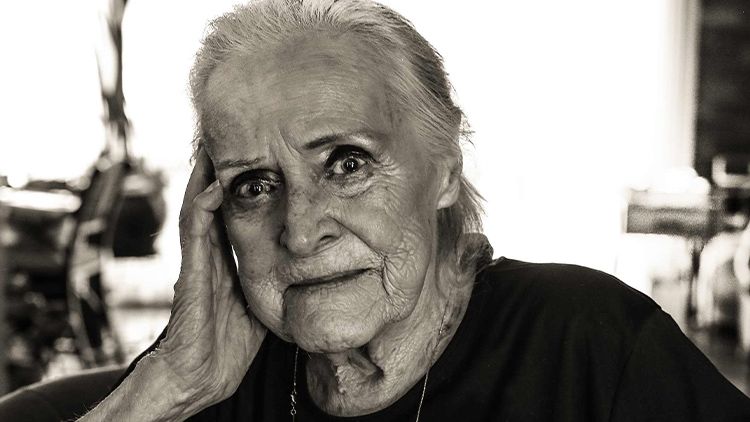

Alex Blain

Alex Blain

SAFE: GIVING PEOPLE A

TRANSPARENT, LEGAL OPTION

Alex Blain had an assisted death in Victoria, Australia in 2021, aged 28. He died just over a year after being diagnosed with a rare and aggressive cancer. His family explain how having the choice of assisted dying ‘saved his life’.

Alex Blain

Assisted dying eradicated his biggest fear - dying of cancer. And to Alex, that was the same as saving his life. It helped him to reframe his situation as ‘lucky’ because he knew there was a way out from his living nightmare.

We’ve come to the conclusion that assisted dying has very little to do with death and a lot to do with life. It allowed Alex to live while he could and it allowed him to take control of his life.

Surrounded by his family and fiancée on the balcony of his riverside apartment, Alex self-administered the medication exactly when he said he would.

He raised the cup, said “f*ck cancer” and quickly drifted into a peaceful sleep.

Alex left us with some final words - including a message to fight for voluntary assisted dying (VAD) laws.

“Advocate for VAD in your state - lives depend on it.”

In the absence of safeguarded choice, some dying people are taking matters into their own hands and ending their own lives in violent ways. Others attempt to end their own lives but worsen their condition.

A desire to protect loved ones from prosecution often leads to dying people ending their lives alone.

There is inconsistency in how these deaths are investigated and recorded. When investigations do occur, they are traumatic for family members and first responders.

These deaths still occur when people are receiving specialist palliative care.

- In a study commissioned to inform the assisted dying debate, the Office of National Statistics found that people with severe and potentially terminal health conditions, including low survival cancers, are around twice as likely to die by suicide than a matched control group.

- Based on research and localised studies of coroners records, Dignity in Dying estimates that up to 650 dying people end their own lives every year.

- Dying people are using the dark web to access drugs to take their own lives. This requires people to have a degree of digital literacy and internet access. The lack of regulation and oversight means this is a dangerous option which exacerbates inequalities.

RECORDED SUICIDES AND SPECIALIST PALLIATIVE CARE

Background

In April 2023 Dignity in Dying sent a Freedom of Information (FOI) request to NHS trusts and Health Boards in England, Wales and Scotland. This FOI requested data on the number of suicides and suicide attempts recorded amongst patients receiving specialist palliative care, including in NHS specialist palliative care units.

Results

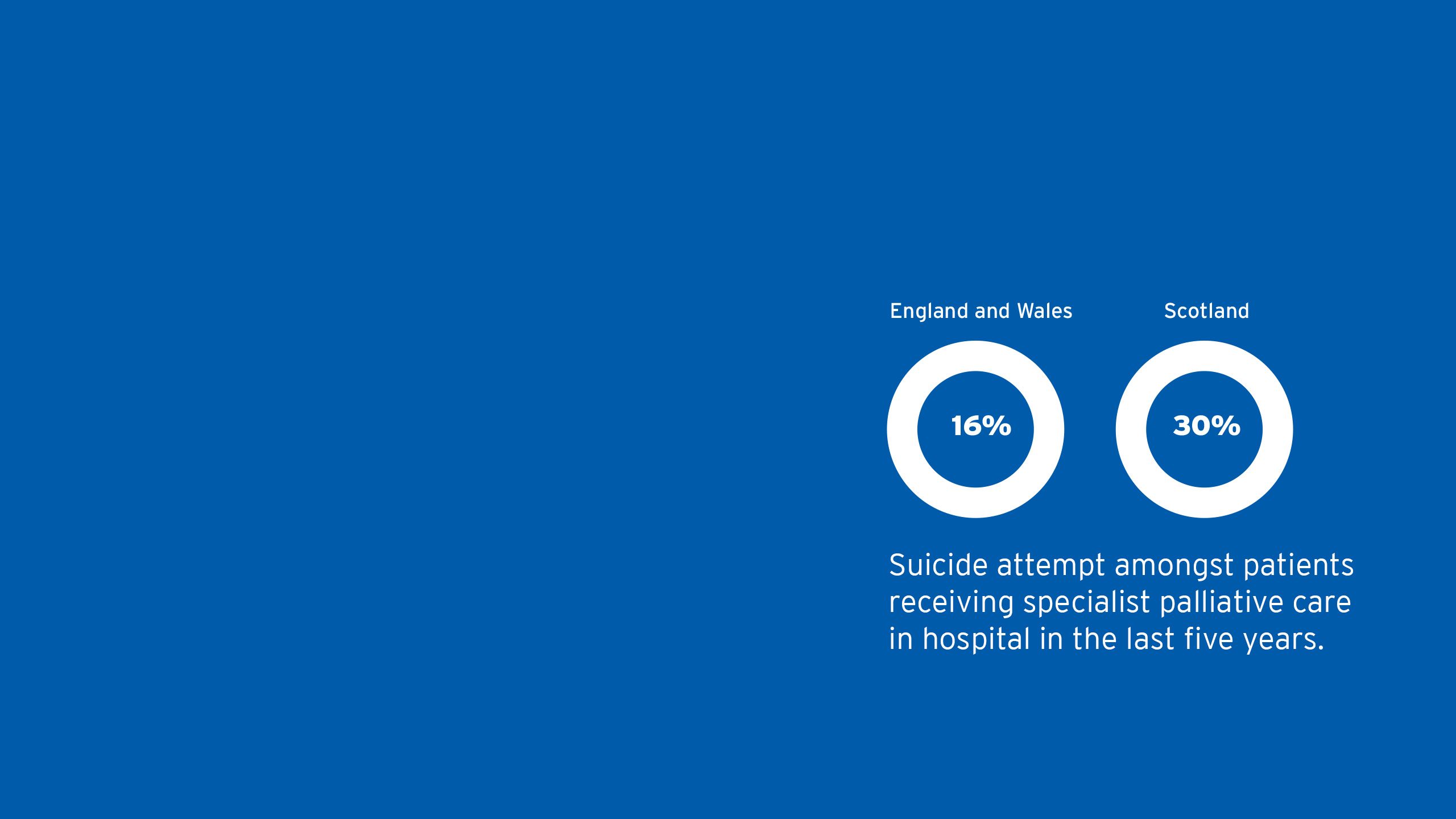

In England and Wales 13 out of 80 Trusts that recorded this data (16%) had a record of at least one suicide or suicide attempt amongst patients receiving specialist palliative care in hospital in the last five years.

In Scotland 3 out of 10 (30%) Health Boards that recorded this data had a record of at least one suicide or suicide attempt amongst patients receiving specialist palliative care in hospital in the last five years.

Next steps

This data adds to the evidence-base of the lengths dying people go to exercise control even when they have access to specialist palliative care. Due to the limited data that is publicly available and inconsistent reporting, we do not know the exact number people receiving specialist palliative care who end their own lives. The data also excludes charities that provide specialist palliative care, such as hospices, though there is anecdotal evidence that suicides in hospices do occur.

We urge NHS Trusts, Health Boards and hospices to routinely monitor and publish this data in order to inform debates around end-of-life choice.

Before law change in Australia, a number of inquiries into end-of-life choice prompted research into the number of terminally ill people who ended their own lives every year. The situation was recognised as unacceptable and was a key factor in law change.

Legislating for assisted dying has provided a safe, legal, transparent option for terminally ill people. It has prevented dying people from ending their own lives in violent ways.

Implementing clear, upfront safeguards means that legalising assisted dying has protected potentially vulnerable people far more than was possible under a blanket ban.

- Before legalisation, parliamentary inquiries into end-of-life choice in Australia received evidence that 10-15% of recorded suicides were by terminally ill people, similar to current estimates in the UK.

- In Victoria, coroners reported the most frequent methods used by this cohort were poisoning, hanging, firearms and suffocation. In response to a question about whether palliative care or other support services could prevent such suicides, coroner John Olle said “the people we are talking about in this small cohort have made an absolute clear decision. They are determined. The only assistance that could be offered is to meet their wishes, not to prolong their life.”

- People who have an assisted death in Australia and the US tend to be over 65, have cancer, be highly educated and were receiving palliative care. In all jurisdictions that have changed the law, potentially vulnerable groups are underrepresented in the figures for those who access assisted dying.

“I have used assisted dying to introduce patients to palliative care and improve their symptom control, and I have had several cases where traumatic suicides have been averted because of the availability of this process.”

UNFAIR: IGNORING THE LIMITS OF END-OF-LIFE CARE

Alison Trotter, from Buckinghamshire, died of head and neck cancer in a hospice in June 2021. She had three major operations to remove tumours in her upper and lower jaws, as well as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Her husband Danny describes how, despite receiving good care, Alison died a painful death.

Danny Weidenbaum with a photo of his wife Alison

The care Alison received in the hospice was outstanding, but her pain and symptoms could not be relieved. The cancer had eroded much of one side of her face leaving a very large hole that prevented her from eating and drinking. She also could not be intubated because the tumour had blocked her nostrils.

She reached a point where she said she wanted to die and her medical team said they would increase her dose of pain relief to alleviate any further suffering. However, this made little difference as she had developed a tolerance to her opiate painkillers. Her pain management drugs made her sleepy but she still continued to wake up in agony. At one point she wrote ‘help’ on a piece of paper.

I felt completely powerless.

It took her 15 long days of suffering for her to die. This terrible experience left our family traumatised. Sadly, we came to realise that the very best palliative care she had received at the hospice could not in itself have prevented her suffering.

Danny Weidenbaum with a photo of his wife Alison

Danny Weidenbaum with a photo of his wife Alison

Laraine Blackson

Laraine Blackson

FAIR: BRINGING END-OF-LIFE CARE INTO THE 21ST CENTURY

Laraine Blackson had an assisted death in Victoria, Australia in 2022. She was suffering from cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Laraine’s cousin Fran explains how Laraine used assisted dying to avoid suffering at the end of her life.

Laraine Blackson

Laraine had said: “If there was a glimmer or possibility to survive my illness and live I would. I love life. I love people. But this is not living. You must allow the personal privilege of dying with dignity. Where I am at now is not dignified. It is pure pain and suffering.”

As her cancer and COPD worsened, the voluntary assisted dying (VAD) substance in Laraine’s cupboard brought peace of mind. “My biggest fear is choking to death – that’s terrifying. VAD has allowed me to avoid that at all costs,” she said. We said our goodbyes and I had my arm around her. She swallowed the mixture in one gulp. She said, ‘It’s just a medicine that’s going to make me better.’ They were her last words. She was unconscious within 10 seconds and the doctor declared her death 15 minutes later.

Thanks to the UK’s world-leading palliative care, most people who die will have their symptoms well-managed at the end of their lives.

Yet a majority of people know someone who has suffered as they died. This is because even the best palliative care has its limits.

A small but significant minority of people will experience unrelieved pain and other symptoms at the end of their lives. More palliative care would not stop this from happening.

Existing end-of life practices are ethically complex and have relatively little formal guidance, regulation or oversight.

Decisions to hasten death are sometimes made behind closed doors and are led by doctors, not dying people.

- 57% of people in England and Wales have seen a loved one suffer at the end of life. (YouGov 2023)

- The Office of Health Economics estimates that even if every dying person who needed it had access to the level of care currently provided in hospices, 6,394 people a year would still have no relief of their pain in the final three months of their life. This equates to 17 people every day.

- Pain is just one symptom of dying. Other symptoms such as nausea, constipation, fungating wounds, terminal haemorrhages and faecal vomiting can be difficult to prevent and manage. Research shows these symptoms can have a devastating impact on dying people.

- In an effort to control their deaths, some dying people refuse treatment that is keeping them alive. Others refuse food and water to actively accelerate their deaths, both of which are legal end-of-life options under the current law. In these circumstances, doctors are responsible for checking the person has mental capacity and is not being coerced into making the decisions, but there is no formal process to ensure this happens.

- Palliative sedation is often used to make dying people unconscious, often up until the point of death. Research shows dying people and healthcare professionals think palliative sedation can blur the lines between end-of life care and assisted dying. There is no formal oversight of how often palliative sedation is used, but in one study 17% of doctors said it was used in the last death they attended.

- A 2009 study of UK doctors found 7.4% reported they had made decisions with, to some degree, the intention to hasten a person’s death.

Seventeen people a day will suffer as they die.

Evidence from a number of jurisdictions shows that palliative care and assisted dying work effectively together. Assisted dying legislation adds clarity to the law and this has encouraged honest and open conversations between dying people and their doctors.

- Prior to law change in Australia, the government-funded Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration published data from over 100 palliative care services which showed that 4.9% of patients experienced severe physical pain in the last few days of life.

- A 2018 report commissioned by Palliative Care Australia which examined assisted dying around the world found “no evidence to suggest that palliative care sectors were adversely impacted by the introduction of legislation. If anything, in jurisdictions where assisted dying is available, the palliative care sector has further advanced.”

- Since law change across Australia there has been a huge boost in funding for palliative care, totalling the equivalent of over half a billion pounds.

- Data from Australian States shows over 80% of people who access assisted dying received palliative care. In Oregon, 9 out of every 10 people who have had an assisted death since 1997 were enrolled in hospice care.

- Assisted dying is the most well monitored aspect of end-of-life care. Data is collected routinely and reported on annually to ensure use of the law is safe and transparent.

- The detail of data on exactly how assisted dying works is unprecedented compared to other practices such as palliative sedation or the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

- For example, we know that in Oregon the average time to unconsciousness when someone self-administers the life-ending medication is around 5 minutes and the average time to death is around 30 minutes.

- Oregon is in the top 25% of States in terms of hospice use. Research has found law change has “resulted in or at least reflects more open conversation and careful evaluation of end-of-life options, more appropriate palliative care training of physicians, and more efforts to reduce barriers accessing hospice care.”

“End-of-life care in Australia is now safer and fairer than ever before. We have brought behind-closed-doors practices into the open and given dying people meaningful, transparent choices. Crucially, none of the fears that were put forward as reasons not to change the law have been realised. The status quo was broken. Assisted dying works.”

- ALEX GREENWICH, MP FOR SYDNEY

UNREGULATED: OUTSOURCING DEATH TO SWITZERLAND

Adrian Shooter, from Oxfordshire, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) in 2021. Adrian’s wife Barbara describes his final weeks.

Barbara Shooter with a photo of her husband Adrian.

MND is a brutal disease. Before he died, Adrian used a ventilator at night, but still woke up gasping for breath, his speech and ability to swallow were deteriorating and he lost a huge amount of weight. He knew that he was only going to get worse and chose to go to Switzerland to regain the control over his life and death that MND had stolen from him.

After he was approved, he became almost buoyant, knowing that there was an end to his suffering in sight. Adrian’s death was peaceful and pain free. He died in my arms.

We knew that I was breaking the law by helping him, but I wanted to support him. I’ve never been spoken to by the police. There was no oversight of what we did. We shouldn’t have been forced to travel while Adrian was very sick or spend £12,000 to give him control over his death, a sum of money out of reach for many people. Adrian should have had the right to die at home, in his own bed, not in a foreign country hundreds of miles away."

Barbara Shooter with a photo of her husband Adrian.

Barbara Shooter with a photo of her husband Adrian.

Stephen Boeyen

Stephen Boeyen

REGULATED: CREATING LAWS

THAT EMPOWER AND PROTECT

Stephen Boeyen had an assisted death in Western Australia in 2021. He was one of the first people to use Western Australia’s Voluntary Assisted Dying law.

Stephen Boeyen

Stephen’s wife Lisa describes what being able to die at home meant to him.

On the day, we had breakfast together as we normally do. The doctor arrived first and then our family. I didn’t need to ask how Stephen felt; I knew he was comfortable with his decision. Cancer had been torturing Stephen for months.

What a beautiful way to spend your last hours, chatting and saying final goodbyes with your family, music of your choice playing in the background, wearing clothes you chose to wear that day, passing in a safe environment comfortable to you.

I personally can’t think of anyone telling me they had hugged or thanked their doctor when a loved one died, nor the dying person doing the same. We did.

It is not easy to lose someone dear to you. Stephen and I had been together for 35 years. But perhaps my account of the process helps you understand that it was a very peaceful, calm, safe environment for someone to end their life.

People are already dying. Let them die with dignity.

At least 632 Britons have had an assisted death in Switzerland.

The only safe option for British people who want assistance to die is to travel to Switzerland. However there are several obstacles that place this out of reach for the majority.

The financial cost of this option has created a two-tier system of dying in the UK, where only a privileged few are able to access safe, legal assistance. Even for those who can afford to access assisted dying overseas, many people die much sooner than they want to, because they must be well enough to travel.

The difficulty of organising an assisted death overseas and the threat of prosecution for loved ones is traumatic for all involved.

Guidance for doctors in the UK is unclear, which results in inconsistent care. The lack of regulation and oversight means the current law is incapable of protecting vulnerable people.

- British membership of Dignitas, perhaps the best-known Swiss assisted dying organisation, is at an all-time high, having increased 80% over the last 10 years.

- It is a crime to assist someone to travel overseas for an assisted death, even to a place like Switzerland where assisted dying is legal. The Crown Prosecution Service guidance makes clear that the likelihood of prosecution for loved ones who provide compassionate assistance is low, but the threat of 14 years imprisonment remains. Police investigations and the threat of prosecution are extremely traumatic for those involved.

- The average cost of travelling abroad for an assisted death in Switzerland is £15000. This cost has increased by 50% in the past 5 years. 63% of people in England and Wales cannot afford this.

- There is insufficient oversight of these deaths. Investigations often occur after the fact and crime data for England and Wales shows that there were evidential difficulties in over half the cases of ‘aiding suicide’ recorded in recent years. Only 182 cases were referred to the Crown Prosecution Service between 2009 and 2023.

This is significantly fewer cases than there were British assisted deaths in Switzerland in the same time period, highlighting blind spots in the current law. - The General Medical Council and the Medical Defence Union give doctors conflicting advice about what support they can give people who are arranging an assisted death in Switzerland. This results in inconsistent practice and creates anxiety for dying people, their families and those who care for them.

Assisted dying laws empower people to make decisions about how, when and where they die. The vast majority of people who have an assisted death die in familiar surroundings at home. In contrast to many deaths in hospitals and hospices, people who have an assisted death have a clear opportunity to say goodbye to their loved ones. Because people who have an assisted death are not sedated before they die or receiving large doses of pain relief, they retain clarity of thought up until the end of their lives.

• Where assisted dying laws for terminally ill people are in place, assisted deaths account for around 1% of all deaths.

• By far the most common concerns for people who access assisted dying are being less able to engage in activities making life enjoyable, losing autonomy and losing dignity

• Assisted dying gives people peace of mind. Most people who ask about the option of assisted dying do not go on to use it. Around a third of people who go through the assessment process and are approved do not go on to take the medication.

• The Oregon Hospice Association says “Oregonians need not choose between hospice and physician-aid in dying. Dying Oregonians can choose both from among the options on the end-of-life continuum of care.”

• In Oregon, 9 out of every 10 people who have had an assisted death since 1997 died at home.

• Australian membership of Dignitas has decreased in recent years.

Bringing forward this debate is a matter of urgency for Parliament.

Further delay causes intolerable suffering for dying people and their loved ones.

It is time for Westminster to have this debate.

It’s time we did better for dying people in the UK.

A more detailed version of this report is available here:

To find out more about the data collated in this report and the evidence cited, please visit: http://www.dignityindying.org.uk/timeforchoicereferences